It wasn’t until she was in prison, serving a life sentence for a murder, that Ny Nourn learned the full extent of what her mother went through during the Cambodian genocide. But by then, without ever realizing it, Nourn had lived a life that echoed her mother’s.

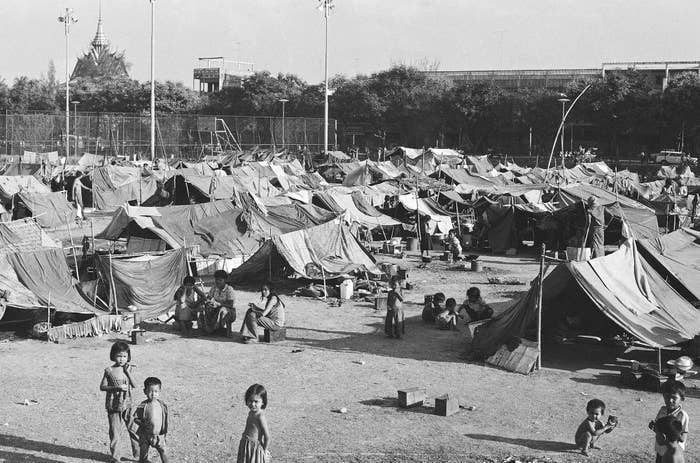

Like so many Cambodian Americans of her age, Nourn arrived in the United States with her mother when she was just a child. Her only memories of the collective trauma her people endured after the Khmer Rouge seized power in 1975 were vague wisps of the hunger and cold she experienced in the refugee camp where she was born.

As it was for so many Cambodian Americans of her generation, the genocide became an ever-present cloud that hung overhead, darkening the shadows but never directly discussed.

“We as refugees, we come from places of trauma,” Nourn said. “But my mother, she would never tell me about the horrors that she witnessed.”

Studies have thoroughly documented the long-term effects that the genocide has had on survivors who resettled in the US: post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, diabetes, and hypertension. But for many in the Cambodian American community, the mental health of the survivors fell to the wayside as they faced more immediate concerns upon their arrival in the US: assimilating into a new country where few looked like them and they could barely speak the language, all while learning how to survive with little money in a wealthy country. The children of these survivors grew up never comprehending why some of their parents could not stand the sound of fireworks or airplanes, or the roots of the abuse they experienced in their households.

As Ny and many other children of refugees found acceptance through gangs or violent partners, the Cambodian genocide shattered another generation. Now, as the contours of their inherited traumas become clearer with age, they stand on the front lines of efforts to end a destructive cycle that began spinning before they were born.

“The thing with genocide is that it will continue,” said Theanvy Kuoch, a survivor and founder of Khmer Health Advocates in Connecticut. “With genocide, there is no past tense.”

Ny Nourn was born in a refugee camp to a mother who had fled the Khmer Rouge on foot at the age of 18. Pol Pot had seized the capital Phnom Penh six years earlier, stepping into a power vacuum left by civil war and the US military’s targeting of North Vietnam.

The Khmer Rouge sought to eliminate the country’s ethnic minorities and educated class and forced much of its populace into agricultural work camps that led to widespread famine and death. By the time the Vietnamese army toppled the Khmer Rouge in January 1979, the regime had killed at least 1.5 million people — nearly a quarter of the country’s population. In the aftermath, survivors found their way back from the work camps to their homes. Some began the treacherous trek through the jungles to refugee camps in Thailand.

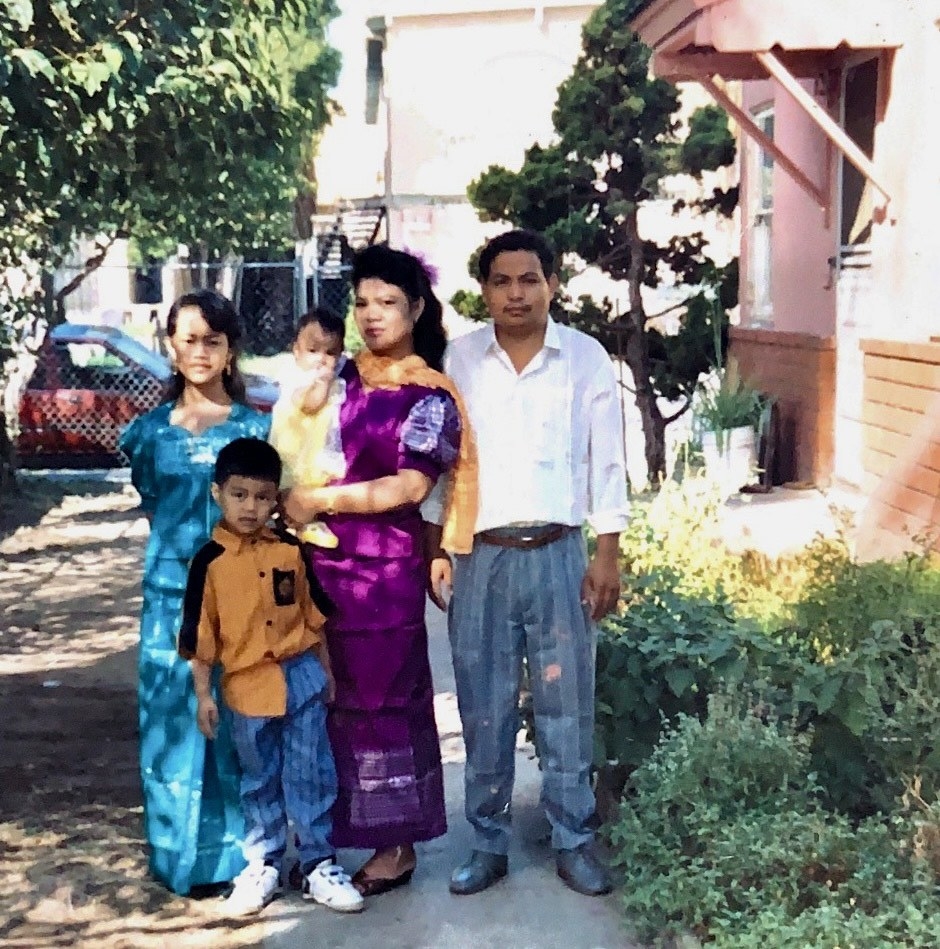

Nourn’s mother met her father at one such camp. But he abandoned both of them before her first birthday, so it was just the mother and daughter who traveled to the US in 1985. They were among the 195,000 Cambodian refugees who resettled in the US between 1975 and 1999.

Within a year after their arrival in the States, her mother had met and married Nourn’s stepfather, a Vietnamese refugee. Nourn spent her youth watching her stepfather hit her mother and control her decisions. She spent her teenage years hiding the knives in the kitchen and physically putting herself between her stepfather and her mother to prevent him from beating her.

Her stepfather demanded that her mother be stricter with her, and her mother responded by slapping Nourn in the face and beating her with wire hangers. When her younger sister and brother were born, Nourn found herself stepping into the demanding translator and pseudo parental role that often befalls the eldest children of immigrant families. Nourn had to take care of her siblings when her mother was too physically and emotionally hurt from the violence to get out of bed — feeding them, bathing them, and getting them ready for school.

Nourn remembered feeling lonely in her youth, with her family moving across five homes around the San Diego area. She had trouble opening up to her peers because she felt like she had to hide the abuse going on at home. As she got older, she found comfort in talking with men, meeting strangers in internet chatrooms. In 1998 — at the age of 17 — she escaped the violence at home by entering a relationship with a married man 20 years her senior.

He quickly became abusive, starting with acts of control that included displays of jealousy and demands on what she should wear. She believed that as long as he wasn’t laying hands on her, it wasn’t abuse — but then he started hitting her, and then raping her.

“I told myself before, witnessing that violence between my mom and stepdad, I would never find myself to be in an abusive relationship,” she said. “But the only relationship that was modeled to me going out into the world was their relationship.”

When Nourn was 18 — still in high school — the 38-year-old supervisor at her after-school telemarketing job asked her on a date and they began seeing each other. When her boyfriend found out, he flew into a rage and forced her to lure the man out to a deserted area, she said.

Nourn said she didn’t know that her boyfriend meant to shoot and kill him, but that’s what he did. He threatened to do the same to her and her family if she told anyone, she said.

She spent three years living with guilt and fear, her boyfriend continuing to beat and terrorize her. In 2001, she confided in two coworkers who had noticed her bruises, and they encouraged her to contact the police about the killing.

Prosecutors charged her and the man, now her ex-boyfriend, with murder. They argued that even though she did not pull the trigger, her ex-boyfriend would not have killed the victim had it not been for her. Even if she had been in fear for her life, they said, duress is not a defense against murder.

At her 2003 sentencing, the judge described her ex-boyfriend as a “mad dog” but said it was Nourn who had “let him off a leash.” At the age of 21, Nourn ended up receiving the same sentence as her ex-boyfriend: life without the possibility of parole.

In prison, Nourn couldn’t help noticing that more and more Southeast Asians were filling the cells around her. From 1977 to 1997 — a period when the Asian population in the US tripled — arrests of Asian American and Pacific Islander youth increased across the country by 726%. Nourn and hundreds of thousands of other children of Southeast Asian refugees would come of age amid America’s “tough on crime” era, as the overall attitude toward criminal justice prioritized punishment over rehabilitation.

Their generation arrived in a country that looked and treated them very differently than what their parents had grown up expecting of the new world. The immigration wave coincided with an economic crisis that led to a rise in crime across the country. After their arrival in the US, Cambodian refugees ended up dispersed throughout the lower-income neighborhoods of Long Beach, Los Angeles, and Oakland in California; Lowell, Massachusetts; and Philadelphia — fighting for scarce resources alongside Black and Latino communities.

Borey “Peejay” Ai, who was also born in a Thai refugee camp, grew up in the lower-income Oak Park neighborhood of Stockton, California, after his family arrived in 1985.

He has distinct memories of hearing the sound of gunfire and his mother pulling him and his siblings under the kitchen table — and of the racist violence he experienced and witnessed around him.

“Adults would spit on us and tell us, ‘Go back to your country,’” Ai said.

When Ai was 8, a man with a public hatred of Asian immigrants opened fire with an assault rifle on primarily Cambodian and Vietnamese immigrant children at Cleveland Elementary School, where Ai was a student. His 7-year-old cousin was among the five kids killed. “I actually watched my classmates gunned down in front of me and I still remember it like it was yesterday. That was the moment that changed the trajectory of my life,” he said. “I stopped feeling safe.”

He said his father was absent for much of his childhood, having turned to drugs to cope with his memories of the genocide. Ai feared sharing details of the discrimination he faced and burdening his mother, who would recount for her children her horrific experiences from her past. “My mom would watch TV and see all these white people feeding the whales and saving abandoned dogs and stuff. She came to the country feeling like she had been saved,” Ai said. “But we experienced it differently from her.”

For Ai, joining a gang at the age of 12 was his way of finding people who understood what he was going through. “I grew up with all this hatred and resentment toward everything, and the gang provided an escape and showed me love,” he said. “The older gang members — the homies — they would hug us, tell us they loved us, cared for us. They showed up when we were getting picked on. As a kid growing up who wasn’t feeling loved, that was everything. The gang became my family.”

When he was 14, Ai and three other gang members set out to rob a convenience store in San Jose. The plan went off course, he said, when the store owner grabbed the gun from him. Ai pulled the trigger, striking the owner through the neck and killing her. He was tried as an adult and sentenced to life in prison.

“As children, as teenagers, how could we help our families when we were trying to deal with it ourselves?” Nourn said. “We’d stay away from the home, the violence that was going on at home, the trauma that our parents were experiencing, because we were dealing with our own experiences living in the US.”

Nourn’s mother took it hard when she was arrested, blaming herself though never explaining why. When Nourn went to prison, her mother began calling her at least twice a week. “Before my incarceration, we couldn’t have a normal conversation,” she said. “My mother never really had a healthy conversation with me. She would always talk at me.”

The other women incarcerated with Nourn had told her about the support group for domestic violence survivors in prison. Hearing about other women’s experiences, she opened up about her own. She met with a therapist and started understanding how the trauma and violence of her upbringing shaped her feelings, relationships, and actions.

Throughout this self-discovery, her mother would ask her pointed, leading questions in their phone calls that seemed to apply not just to Nourn but herself: “How did you end up in that violent type of relationship?” “In a way, she was asking, how could you just not walk away? And then I’d say to her, ‘Well, remember, Mom, you tried to leave like that many times. But you always came back,’” she recalled.

Nourn appealed her case on the grounds of battered woman syndrome, and in 2006 her sentence was reduced to 15 years. As Nourn prepared to go before the parole board in 2017, her mother sent her the letter she planned to give the parole board to argue for her daughter’s release. In it, she blamed herself for not being a good mother and not providing Nourn with a good upbringing due to her own unprocessed trauma.

In their phone calls, she told Nourn of her years of constant fear. She told her daughter how she didn’t think she would survive the perilous journey of land mines and muddy rivers to Thailand, trudging for days on foot along roads that often took her past dead bodies. But it wasn’t until the parole letter that Nourn’s mother revealed a secret she had kept hidden almost her entire life: that when she believed she had finally arrived to safety, she was gang-raped by Thai soldiers at a refugee camp. “I remember reading the letter over and over again, and just crying,” Nourn said. “Then I got on the phone with her, and she told me the only other person who knew about this was my stepfather.”

Nourn added, “My mother told me, ‘I’ve only been with two men in my life. That’s your father and your stepfather.’ She was a virgin when she was raped. She told me, ‘I really don’t know what love is. Any man that I got with, it was not out of love. It was for protection.’”

Mary Scully has encountered numerous situations just like Nourn’s in her decades counseling families through Khmer Health Advocates in Connecticut. The kids acted out against their parents who just didn’t seem to understand when, in fact, it was the reverse: the kids didn’t understand their parents.

“The parents go from either being overprotective or to being numb and not there,” Scully said. “And, you know, kids are like a bouncing ball. They could feel close to their parents one minute, and the next minute if the parent freezes and is dealing with their trauma, they're emotionally cut off. That's really confusing for kids.”

Scully once counseled the family of a teenage boy causing trouble at school. The boy’s mother had a mental illness, and the son confessed during a family counseling session that he felt like he had made her sick. His father and sister, in tears, told him that he had actually had a twin and that during the genocide his mother had to choose which of the babies would survive because she couldn’t feed both. “It wasn’t your fault,” they told him. “It was the Khmer Rouge.” Scully said after that, the boy stopped causing trouble and went on to graduate from high school and college.

“It’s not just the one story that fixes it,” Scully said. “It’s being able to talk about it.”

Khmer Health Advocates, which came together in the immediate aftermath of the genocide, provides healthcare for Cambodian American refugees. It was around this time that the American Psychiatric Association began finally recognizing and studying PTSD, in particular among Vietnam War veterans. But what the founders of Khmer Health Advocates discovered in their community-based approach was that mental health was not a primary focus for refugees at that time; many were more concerned with the immediate challenges before them, such as reuniting with the rest of their family members who were still in Southeast Asia. For years, these refugees focused only on their survival and that of their loved ones. To allow for a moment of humanity to process what they actually experienced and witnessed could derail everything.

Khmer Health Advocates’ founder, Theanvy Kuoch, more than understood that sentiment. The Khmer Rouge had detained and killed her husband. When the soldiers tried to take her 5-year-old son from her, she knew if she fought to keep him that they’d kill both him and her, so she forced herself to stand still — only the sheer will of the little boy gripping his mother’s legs allowed them to stay together. When every one of her remaining family members, except her son and niece, died from starvation or illness, she could not give herself to grief. Not even when fighting separated her from her son after she made the trek to a Thai refugee camp in search of food — a journey so strenuous that all her toenails fell off — did she let herself feel anything except fear.

It wasn’t until she had safely made it to San Francisco that all the emotions hit her at once. “When am I going to see my family again? When am I going to see my son?” she said. “I was in tears.”

On top of that, a strong cultural stigma around mental health still exists today.

“Our culture sees mental health as a weakness, or seeking for attention,” said David Bunna, a case manager for the Cambodian Family Community Center in Santa Ana, California. “That creates a silence of not wanting to speak because I don’t want to show my weakness.”

But not addressing the trauma has consequences. Stress and trauma have been linked to the development of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. A 2016 study found that Cambodian refugees were much more likely than the general population to suffer from diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia.

Amina Sen-Matthews, the center’s health program director, never got to talk to her parents in depth about what they experienced in Cambodia before they died: the constant terror of the civil war, the fight to stay alive during the genocide, the two children they lost to malnutrition. “My parents passed away in their early 70s,” Sen-Matthews said. “I felt like maybe if they were able to process everything, I don't know, maybe they would have been here longer.”

She remembered one time her parents commented after an airplane flew overhead that when they used to hear something like that, they would have to run for the dugouts and bomb shelters. “We lived by John Wayne Airport,” Sen-Matthews said. “How much trauma was that giving them? How triggering was it, to hear those planes and not to be able to process all of that?”

In her work, Sen-Matthews has come to understand that her program needed to take a different approach to processing trauma than just offering Western prescriptions like counseling and talk therapy. For some in the community — elders in particular — good mental healthcare just looks like community care. For them, good mental healthcare involves potlucks, trips to the beach, dance classes, and group exercise — being with and supported by a community. Here, as they start feeling more comfortable, they begin opening up, remembering pieces of the past, and sharing memories. Next comes mental health workshops and therapy with counselors who speak Khmer, the official language of Cambodia.

Sen-Matthews has come to learn that the family dynamic within Cambodian culture is one that is intrinsically close-knit. Multiple generations live in the same households. When there is a problem with one member, relatives first look within the family to seek help.

It’s a dynamic that has made the generational trauma so much heavier — and it’s one that can present paths to solutions.

But just as the children of survivors are finding their way back to their people, as thousands of individuals who were incarcerated in their youth are now being released from prison, a new trauma is taking root in the community.

Under the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996, immigrants — including green card–holding refugees — can be deported if convicted of certain crimes. Of the at least 16,000 Southeast Asians in the US who received final deportation orders in 2018, more than 13,000 were based on past criminal records. “These individuals have served their time, oftentimes decades, for crimes committed when they were young people, when they were teenagers,” said Angela Chan, an immigration attorney with the San Francisco Public Defender’s office.

In May 2017, after 15 and a half years, Ny Nourn was released from prison. Her first taste of freedom was having her legs and wrists shackled by a private security guard, who escorted her into an unmarked white van. The US government was trying to deport her to Cambodia, even though she had never stepped foot there. After six months in a California county jail that rented space for ICE, Nourn was released on a $10,000 bond that was raised through a fundraising campaign among friends, relatives, and neighbors.

Peejay Ai, the former gang member from Stockton, served almost 20 years in state prison for the crimes he committed when he was 14. Upon his release in 2016, he was taken into federal custody. He was released on bond in 2018 and has worn an ankle monitor since.

“It’s a reminder that my life’s in limbo,” Ai said. “Any day they can come and get me, pick me up, put me back in prison, and then deport me.”

There are few ways to fight a deportation based on a prior criminal conviction. One is to secure a pardon from the governor. Since they’ve been released on bond, Ai and Nourn have been working with activists and others in the Cambodian American community to petition California’s governor to pardon not just them but dozens of other immigrants in similar situations. In 2018, Ai received a pardon from then-governor Jerry Brown, but it was blocked at the last minute by the state Supreme Court; the justices offered no explanation but called it an abuse of power. Ai is still hoping for a pardon from Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Nourn submitted her pardon application in September 2019. When she received the phone call from Newsom’s office congratulating her on her pardon, she began to shake with excitement. Her first phone call was to her mother. When Nourn explained to her that the pardon meant she was no longer at risk of being deported, her mother began to laugh and cry at the same time.

Nourn is now the executive director of the Asian Prisoner Support Committee, where Ai works as a reentry navigator for individuals recently released from prison. They’ve continued their advocacy, speaking everywhere from the state capitol in Sacramento to Washington, DC, about the plight of their generation of Cambodian refugees.

Nourn recalled that for one demonstration, her organization spoke to the community elders and got them on a bus to Sacramento. “The elders didn’t really understand what was going on, but they knew that, yes, I can help protect my grandson or my brother,” she said. At the capitol, they held signs, danced, and chanted for Newsom to protect their loved ones from deportation. “The youth, they saw that, the elders fighting for their dads or their uncles, and then the youth wanted to get involved,” Nourn said. “And it was really beautiful just to witness: youth and elders and all these three generations, working together.” ●