Secret files obtained by BuzzFeed News reveal that from 2011 to 2015 at least 319 New York Police Department employees who committed offenses serious enough to merit firing were allowed to keep their jobs.

Many of the officers lied, cheated, stole, or assaulted New York City residents. At least fifty employees lied on official reports, under oath, or during an internal affairs investigation. Thirty-eight were found guilty by a police tribunal of excessive force, getting into a fight, or firing their gun unnecessarily. Fifty-seven were guilty of driving under the influence. Seventy-one were guilty of ticket-fixing. One officer, Jarrett Dill, threatened to kill someone. Another, Roberson Tunis, sexually harassed and inappropriately touched a fellow officer. Some were guilty of lesser offenses, like mouthing off to a supervisor.

At least two dozen of these employees worked in schools. Andrew Bailey was found guilty of touching a female student on the thigh and kissing her on the cheek while she was sitting in his car. In a school parking lot, while he was supposed to be on duty, Lester Robinson kissed a woman, removed his shirt, and began to remove his pants. And Juan Garcia, while off duty, illegally sold prescription medication to an undercover officer.

In every instance, the police commissioner, who has final authority in disciplinary decisions, assigned these officers to “dismissal probation,” a penalty with few practical consequences. The officer continues to do their job at their usual salary. They may get less overtime and won’t be promoted during that period, which usually lasts a year. When the year is over, so is the probation.

Today many continue to patrol the streets, arrest people, put them in jail, and testify in criminal prosecutions. But the people they arrest have little way to find out about the officer's record. So they are forced to make life-changing decisions — such as whether to fight their charges in court or take a guilty plea — without knowing, for example, if the officer who arrested them is a convicted liar, information that a jury might find directly relevant.

BuzzFeed News’ reporting is based on hundreds of pages of internal police files that, like all disciplinary records, the department keeps secret, citing a controversial state law on “personnel records.” The files were provided by a source who requested anonymity. They were subsequently verified through more than 100 calls to NYPD employees, visits to officers’ homes, interviews with prosecutors and defense lawyers, and a review of thousands of pages of court records.

Over the coming months, BuzzFeed News plans to publish a database with information about the NYPD officers and civilian employees who have received dismissal probation.

The Probation Files pull back the curtain on one of the NYPD's most fiercely guarded secrets.

The Probation Files do not include all officers who received dismissal probation during the years in question. According to the NYPD, of the more than 50,000 people who work for the department, at least 777 officers and an untold number of other employees received the penalty during the five years in question. During the same period, 463 officers were forced to leave or resigned while a disciplinary charge was pending.

But the Probation Files are by far the most thorough accounting of this practice to date. They pull back the curtain on one of the NYPD's most fiercely guarded secrets, providing the most extensive record available of which officers, despite committing serious misconduct, continue to wield tremendous power over New Yorkers’ lives.

New York is one of only three states, along with Delaware and California, that has a law specifically shielding police misconduct records from the public, according to a study conducted by WNYC in 2015. In recent years, the NYPD has doubled down on its stringent legal interpretation of those laws, even as departments around the country face growing public pressure to be more transparent about police misconduct.

In addition to letting some officers off the hook, sources told BuzzFeed News that dismissal probation is also used to punish other officers arbitrarily, for reporting misconduct or just for getting on their supervisors’ bad sides.

"If 10 cops did the same exact thing that was bad, the outcome is different every time. If you’ve complained, forget about it,” said Diane Davis, a former internal affairs investigator who later sued the department for racial discrimination.

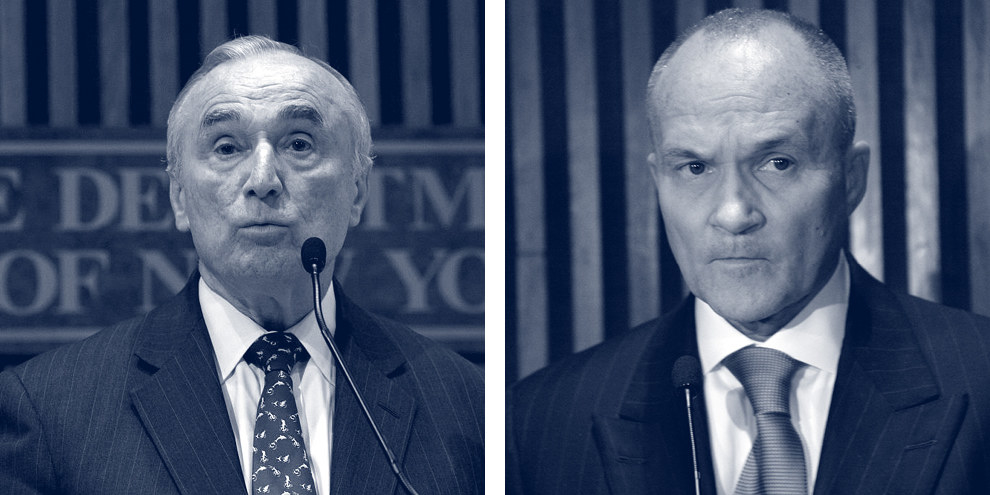

Bill Bratton and Ray Kelly, the NYPD commissioners who ran the department during the years covered by the Probation Files, both declined to speak to BuzzFeed News. (The current commissioner, James O'Neill, took over in 2016.)

BuzzFeed News attempted to reach every NYPD employee named in this story, with phone calls and letters to their homes. Some employees could no longer be located, so we also sent a list of names to both their unions and the NYPD, with the request that those organizations notify the officers of the opportunity to comment. Most officers did not respond.

Speaking for the NYPD, Kevin Richardson, the deputy commissioner of the Department Advocate’s Office, which determines which officers to charge and prosecute at the NYPD’s internal disciplinary trials, said the law prevented him from commenting on specific officers’ cases. But in general, he said, dismissal probation serves a valuable purpose.

“The department is not interested in terminating officers that don't need to be terminated. We're interested in keeping employees and making our employees obey the rules and do the right thing,” he told BuzzFeed News. “But where there are failings that we realize this person should be separated from the department, this police commissioner and the prior police commissioner have shown a willingness to do that.”

Got a tip? You can email tips@buzzfeed.com. To learn how to reach us securely, go to tips.buzzfeed.com.

Richardson added that, since he joined the department in 2014, he has worked to make the process fairer and reassessed the penalties given to officers guilty of misconduct. The department declined to offer any examples of penalties that have changed, or any data that would support his claims.

Asked about the misconduct of his members, Gregory Floyd, the president of the union representing school safety agents, said “that's something that we don't condone.”

Al O’Leary, a spokesperson for the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, the largest police union representing NYPD officers, had a different message: “We’re not going to talk to you about anything negative as far as any of our officers.”

Former NYPD detective sergeant Joseph Giacalone, who spent two years of his two-decade-plus career in internal affairs, said, “Dismissal probation is supposed to be used for somebody who screwed up something big but it wasn’t intentional — they made an honest mistake.”

But any officer who is caught committing an egregious offense, such as lying or stealing department property, should be fired, Giacalone said. “They have broken the trust of the oath that you took.”

“I really don’t want to talk about it.”

During his first six years on the force, officer Raymond Marrero was accused of viciously beating one person, falsely arresting another, assaulting a third, and fabricating evidence against a fourth.

In February 2008, Marrero, an officer in the 52nd Precinct in the Bronx with a stocky build and shaved head, arrested a woman who videotaped him allegedly roughing up her boyfriend. Officers seized her phone, which was never returned. She was charged with obstructing government administration, disorderly conduct, and harassment, but acquitted on all counts. She sued; the city paid her $25,000 without admitting any wrongdoing. The disciplinary documents BuzzFeed News obtained include no record that Marrero faced any punishment.

A few months later, in April, Marrero got into an altercation with a man while issuing him a parking ticket in front of a Toyota dealership in the Bronx. A judge found Marrero’s explanation of why he arrested the man, who later claimed he was thrown to the ground and punched repeatedly in the head, to be “incredible.” All charges against the man were dropped and the city settled his lawsuit for $500,000 without admitting wrongdoing. The disciplinary documents BuzzFeed News obtained include no record that Marrero faced any punishment.

Then, in early 2009, a former police department volunteer named Louis Deluca confronted a man who, Deluca found out, had groped his brother’s 17-year-old girlfriend. The man took off with his friends, just as Marrero was pulling up. “I was telling him, 'There's some guys that groped a family member of mine,’” Deluca said. “‘They're right around the corner.’”

Marrero and his partner told Deluca to shut up, Deluca said. Incredulous, Deluca called Marrero a cunt. The officers pushed him to the ground and arrested him, according to a lawsuit Deluca later filed.

Back at the precinct, as Deluca was being taken out of the car, Marrero struck him with his police baton, opening up a gash on the top of his head. Another officer said there was so much blood, they had to clean it up with a mop. It took 12 staples at the hospital to close the wound.

In a deposition, Deluca said Marrero told him “You can’t disrespect us in the street like that.” Deluca received a $398,000 settlement, of which Marrero was ordered to pay $4,000.

All told, by 2014, the city had paid about $900,000 to settle accusations against Officer Marrero.

A year after Deluca’s arrest, Marrero and his partner held a handcuffed prisoner down while another officer stomped on the person’s head. During an internal affairs investigation, Marrero falsely denied that any officer used physical force.

All told, by 2014, the city had paid about $900,000 to settle accusations against officer Marrero.

Publicly, neither he nor the city admitted any wrongdoing.

But in secret, after an investigation into Deluca’s arrest and the stomping incident a year later, Marrero pleaded guilty to multiple department charges, including striking an individual with “no legitimate police purpose,” “making unnecessary physical contact,” and “providing inaccurate, incomplete misleading answers” to department investigators, according to the files BuzzFeed News obtained.

Yet the NYPD commissioner at the time, Ray Kelly, decided that wasn’t a reason to fire him. Instead he was put on dismissal probation and he forfeited 45 vacation days.

Marrero remains on the force today, earning almost $120,000 last year. He continues to patrol the streets, making dozens of arrests since he was found guilty by the department.

BuzzFeed News asked Marrero about his disciplinary history. Speaking by phone, he said that he appreciated the effort to reach out, but added, “I really don’t want to talk about it.”

The Commission to Combat Police Corruption, an organization set up in 1995 to serve as an outside check on the department’s disciplinary process, took a look at Marrero’s case as part of its review of all disciplinary cases that year. (The commission’s reports are anonymized, so it did not name Marrero explicitly. BuzzFeed News was able to identify him by matching details of a January 2009 arrest with the Probation Files and court documents from Deluca’s civil lawsuit.)

The commission determined that Marrero’s actions suggested he “lacked the temperament necessary to be a police officer.” Instead of being placed on probation, it said, he should have been fired. But the commission has no authority to reverse the NYPD’s decisions.

Informed by BuzzFeed News that the officer who beat him with a baton was still on the force, Deluca, who no longer volunteers for the department, was shocked. “You’ve got to be kidding me,” he said. “I was 1,000% sure he was going to lose his job.”

Deluca shook his head and added, “I can’t imagine since that time how many more times he's done this to people.”

“What kind of message does that send?”

The law that hides New York police officers’ misconduct from public view is one of the strictest in the nation. When Civil Rights Law Section 50-a was first crafted, state legislators thought they had struck a reasonable balance between the need for criminal defense lawyers and prosecutors to have access to serious misconduct records and the need to protect officers’ privacy. It hasn’t worked that way.

While advocating for the proposed law more than 40 years ago, John Maye, president of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, which at that time represented 3,000 transit officers, complained that “unverified and unsubstantiated” allegations as well as “confidential information and privileged medical records” about officers were being wrongly disclosed to the public and misused by defendants’ attorneys.

So in 1976, state legislators passed a bill that put the decision to release or withhold disciplinary records in the hands of judges. The idea was that judges would exercise independent discretion, withholding records that served no public interest, and releasing records that people charged with crimes needed in order to be able to defend themselves.

The state law says that “personnel records of police officers ... shall be considered confidential.” Over time, the NYPD, other departments, and police unions have fought to expand what qualifies as a personnel record. For the most part, courts have agreed with their arguments.

When the NYPD stopped publishing the outcomes of disciplinary trials, it initially said it was saving paper.

The Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, which today represents most New York City officers, recently sued the department for making public a video clip of a fatal encounter between officers and an armed man in the Bronx. Body camera footage, the union argued, is part of officers’ personnel records, and therefore confidential. Their lawsuit against the department is ongoing. BuzzFeed News is one of several media organizations that filed a brief to support public access to the footage.

For decades the outcomes of disciplinary trials were made available — if someone knew where to look for them — on a clipboard on the 13th floor of police headquarters. In May 2016, the Legal Aid Society, the largest public defender organization in the country, filed a public records request for all those outcomes. Suddenly the clipboards disappeared. The NYPD, which initially claimed it was saving paper, now says making the disciplinary findings available even to that limited degree was a violation of the 1976 law. Legal Aid sued the department for the records’ release. The case is pending.

Those trials are nominally open to the public, but the schedule and location are not announced and the results are not disclosed. As a result, ordinary New Yorkers have essentially no way to know what goes on in the small, drab room on the 11th floor of headquarters at One Police Plaza, where officers accused of serious misconduct, such as stealing property, false arrest, or excessive force, can fight the charges.

With little outside scrutiny, some officers told BuzzFeed News the internal trials are merely a “kangaroo court,” rife with favoritism, racism, and pressures to just plead guilty. Some said they did not fight their charges out of fear they would face harsher punishment.

The hearings are overseen not by an independent judge but by a top police official who serves at the pleasure of the police commissioner. After hearing evidence, the trial administrator makes a private recommendation about whether the officer should be found guilty and what the punishment should be.

But the police commissioner decides what to do with that recommendation. There are no rules governing that decision. If the trial administrator found the officer’s misconduct serious enough to merit dismissal, the police commissioner can overrule that recommendation.

Despite this broad discretion, Rae Koshetz, who oversaw such hearings from 1988 to 2002, told BuzzFeed News that illegal drug use, anything related to stealing or corruption, and homicide are almost certain to result in termination. Koshetz was surprised and concerned when BuzzFeed News explained that the Probation Files include a dozen cases in which officers who were found guilty of drug use, theft or “knowingly possessing stolen property” were merely placed on a year of dismissal probation.

“What kind of message does that send out to other officers?” Koshetz said.

Lying is supposed to be a hard-and-fast rule that requires mandatory termination. According to the department’s patrol guide, officers who lie about a “material matter” will be dismissed from the department, unless there are “exceptional circumstances.”

Richardson, the deputy commissioner of the department’s internal prosecutor’s office, said he considers lying a very serious offense, but not necessarily grounds for immediate firing. In certain circumstances, such as when an officer shows remorse, the department would opt for “dismissal probation to make sure that this officer and other officers who are watching this realize this is not something that will be tolerated from the police department,” he said.

Among the officers listed in the Probation Files, at least 50 were found guilty of misleading or making “inaccurate” statements in official records, to grand juries, district attorneys, or internal affairs investigators — and yet were kept on the force.

Officer Lisa Marsh, for example, then an officer at the 48th Precinct in the Bronx, covered up a crime and submitted false documents in connection with the investigation. Officer Carlos Reid “provided inaccurate facts” to the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office about an arrest. Detective Jesus Roldan, who currently works in Brooklyn according to payroll records, “made inaccurate statements” while testifying under oath to a grand jury.

Despite the department’s public position that lying won’t be tolerated, all three of these officers, who did not respond to requests for comment, are still on the force.

“Truly outrageous”

False accusations from an officer can be enough to send an innocent person to prison. Earlier this year, for example, a Queens detective was convicted of fabricating drug evidence that sent an innocent man to jail for 52 days. In Brooklyn, allegations of witness and evidence tampering by the former homicide detective Louis Scarcella has led the district attorney to review more than 40 cases. To date, convictions in seven murder cases that Scarcella worked have been overturned — including one case where a wrongfully convicted man spent more than 20 years in prison.

Every day, New Yorkers accused of a crime have to decide whether to take their chances in court or to plead guilty in exchange for lesser penalties. Without a good reason to question an officer's account, many defense lawyers will advise clients to take a plea deal, since juries are more likely to take the word of a cop than that of a defendant. Statewide, more than 98% of people charged with felonies that result in convictions plead guilty rather than go to trial.

Proof that the officer in question had been convicted of lying could shift that calculus. But that proof is all but impossible to get before the defendant must make their decision.

Prosecutors are obligated under federal law to hand over evidence that might exonerate a defendant, though what exactly that includes, and when it must be produced, is up for debate.

Defense lawyers who want to see for themselves what’s in an officer’s disciplinary record must clear several hurdles. First they have to convince a judge that there is something in the officer’s file that’s directly relevant to the crime the defendant is accused of. That is a hard argument to make without already having seen the file. As a result, defense lawyers say they’re flying blind. Dan McGuinness, a criminal defense and civil rights lawyer who has worked in the New York courts since 2006, told BuzzFeed News all he can do is google around for news stories or lawsuits that mention the officer, hoping something has seeped out into public view. “Our hands really are tied,” he said.

There could be so much more “beneath the surface,” McGuinness’s law partner, Adam Perlmutter, added.

If defense lawyers are able to persuade a judge to review the records, there is still the question of whether the judge will approve their release.

Even when ordered by a judge to hand over the material, prosecutors often wait until just before trial to do so, defense lawyers said, taking advantage of loopholes in New York’s discovery laws.

That gives defense lawyers little time — in some cases just a few hours — to investigate the information, review evidence, locate and interview witnesses, and determine whether it will help prove their clients’ innocence.

“They want trial by ambush,” John Schoeffel, a Legal Aid attorney, told BuzzFeed News.

Victims of police brutality face the same uphill battle.

In 2015, Rosie Martinez, a housekeeper at the time, accused two officers of beating her during an interrogation. As part of her civil rights lawsuit, Martinez’s lawyers sought access to the disciplinary files of the officers they believed were responsible.

One of those officers, Sgt. Jason Forgione, had been put on dismissal probation for covering up an illegal search. That lie produced a cascade of bad results: Prosecutors were forced to drop a case against a convicted felon, and New York City taxpayers had to foot the bill for a $33,500 settlement. Neither Forgione, who declined to comment, nor the city admitted wrongdoing.

But despite a judge’s order, the city failed to hand over any of that information. When the judge found out, she blasted the city’s lawyers and the NYPD.

The city’s conduct is "truly outrageous," she wrote, and has irreparably damaged Martinez’s ability to fight her case. The case is ongoing.

“They suffer twice — first at the hand of cops who abuse them and then by a city law department that puts them through the wringer if they have the temerity to sue over it,” said Joel Berger, a lawyer who used to work for the city defending cops in civil cases and now works as a civil rights lawyer.

“The court is therefore left with no confidence that any part of Officer Rios’ testimony can be assumed as true.”

Defendants and victims of police misconduct aren’t the only ones harmed by the decision to keep officers on the force after serious offenses like lying.

Officers who lie can also endanger legitimate police work and force prosecutors or judges to drop charges against people who should go to prison.

A record of false statements “could jeopardize any case the officer was involved in,” said Bennett Capers, former federal prosecutor and Brooklyn Law School professor. “If nothing else, it could require prosecutors to reopen cases to see what role the officer played and whether it impacts our faith in past convictions.”

Officer Luis Rios is one such example. Rios was convicted, in an NYPD trial, of lying. Instead of being fired, he was placed on dismissal probation. Five years later, during the trial of an accused drug dealer facing at least 20 years in prison, Rios was asked about that incident. He did not answer truthfully.

“The court is therefore left with no confidence that any part of Officer Rios’ testimony can be assumed as true,” the judge wrote in a court order. He said he had no choice but to toss the charges for which Rios was the only witness. Instead, the defendant was sentenced to a year on lesser charges.

Officer Rios, who did not respond to requests for comment, remains on the force today.

The cost to officers

The secrecy surrounding discipline can harm officers too.

Outside of public scrutiny, there is no standard for how the NYPD punishes misconduct. Minor infractions may result in a warning in one case and a serious penalty in another.

The police union has pushed to take more control of the disciplinary process and limit the commissioner’s unilateral authority. “We think the disciplinary system is excessive and draconian, but it’s a quasi-military organization, and all of the challenges we’ve made have come back with, ‘The commissioner is the ultimate arbiter,’” said Al O’Leary, the spokesperson for the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association.

Outside of public scrutiny, there is no standard for how the NYPD punishes misconduct.

One unnamed officer described by the Commission to Combat Police Corruption was assigned to a year of dismissal probation — and suspended for 122 days and docked pay for another 30 — for telling a supervisor that, as a single mother, she needed a couple of days to arrange for child care before being assigned to a new post.

Several current and former officers told BuzzFeed News that the department assigned them to dismissal probation, and transferred them to new jobs, after they raised concerns about illegal quotas or discriminatory treatment. Most declined to be named, citing fears of further retaliation.

Damon Porter, who left the NYPD in 2013, was one of the few who agreed to talk and provide BuzzFeed News with a copy of his disciplinary file.

Five years into his 19-year career, he says he joined other Latino officers in a class-action lawsuit alleging discriminatory discipline standards. After that, Porter said, supervisors began writing him up for even the tiniest mistakes, issues they often ignored for other officers.

In May 2012, he was called down to the trial room at One Police Plaza.

While many of Porter’s charges were “relatively minor,” the trial commissioner, Robert Vinal, took him to task for being discourteous to a supervisor and not doing enough to investigate one case. Vinal recommended a year of probation — a significant statement considering that Porter’s partner in that case merely got a reprimand. But Commissioner Kelly felt that dismissal probation was not a strong enough penalty. He decided Porter was no longer fit to be a cop. Because he was one year shy of retirement age, that cost him at least $10,000 a year from his pension.

Just nine months later, Officer Ray Marrero’s rap sheet landed on Kelly’s desk.

Marrero had been found guilty of beating a man with a baton and of lying to the department. But Kelly decided he deserved a second chance. The commissioner signed off on his punishment: dismissal probation. ●

Outside Your Bubble is a BuzzFeed News effort to bring you a diversity of thought and opinion from around the internet. If you don't see your viewpoint represented, contact the editor at bubble@buzzfeed.com. Click here to join our Facebook group and discuss stories that have changed how you see the world, or here for more on Outside Your Bubble.