When he got the last call to come meet with the FBI agents, A.M. allowed himself an uncharacteristic bit of optimism. An immigrant from Pakistan, he had spent the last seven years trying to get a green card, a process that had so far included a series of interviews, three encounters with the FBI, and unexplained bureaucratic delays. Maybe this meeting would bring some resolution?

But when the 37-year-old software programmer arrived at the Homeland Security offices in Dallas that day in August 2014, the conversation quickly swerved. One of the two agents placed a piece of paper on the table and told him to write down the names of all the people he knew who he thought were terrorists.

Bewildered, he said he didn’t know any terrorists. He said he didn’t know about any suspicious activity at all. “We think you do,” the agents replied.

A.M. was quickly becoming alarmed. (Like almost all other immigrants interviewed for this story, he said he did not feel safe allowing his name to be published. A.M. are his initials.) He was a family man, with a highly skilled 9-to-5 job. He had lived in America for nearly two decades. He went to college in America. Why would the FBI see him as a link to terrorism? And weren’t they supposed to be discussing his green card application?

As it turned out, that’s precisely what they were discussing. “We know about your immigration problems,” he recalls one of the agents telling him. “And we can help you with that.” If, they said, he agreed to start making secret reports on his community, his friends, even his family.

Pressuring people to become informants by dangling the promise of citizenship — or, if they do not comply, deportation — is expressly against the rules that govern FBI agents’ activities.

Attorney General Alberto Gonzales forbade the practice nine years ago: “No promises or commitments can be made, except by the United States Department of Homeland Security, regarding the alien status of any person or the right of any person to enter or remain in the United States,” according to the Attorney General’s Guidelines Regarding the Use of FBI Confidential Human Sources.

In fact, Gonzales’s guidelines, which are still in force today, require agents to go further: They must explicitly warn potential informants that the FBI cannot help with their immigration status in any way.

But a BuzzFeed News investigation — based on government and court documents, official complaints, and interviews with immigrants, immigration and civil rights lawyers, and former special agents — shows that the FBI violates these rules. Mandated to enforce the law, the bureau has assumed a powerful but unacknowledged role in a very different realm: decisions about the legal status of immigrants — in particular, Muslim immigrants. First the immigration agency ties up their green card applications for years, even a decade, without explanation, then FBI agents approach the applicants with a loaded offer: Want to get your papers? Start reporting to us about people you know.

Alexandra Natapoff, an associate dean at Loyola Law School who studies the use of informants, said people who are pressured into informing for the government face considerable danger, from ostracism or retribution within their own community to betrayal from law enforcement officers, whose promises the informants are powerless to enforce. BuzzFeed News spoke with six people who had been approached by the FBI, as well as immigration attorneys who said they had represented far more. Some allowed their stories to be published, even with details that could make them identifiable to federal authorities. But they all drew the line at publishing their names, lest they or their families suffer repercussions from their communities.

Beyond the danger that coercive recruitment poses for its targets, it may also mean danger on a broad scale, by hampering America’s ability to detect, derail, and prosecute real threats to national security.

Like 9/11 before it, the mass shooting in San Bernardino cast into stark relief the urgency of guarding against terrorism at home. Over the years, law enforcement authorities have used informants’ tips to foil numerous plots on American soil and to help other countries foil plots of their own. But many critics of America’s counterterrorism operations say the FBI’s heavy-handed recruitment methods actually make it harder to thwart dangerous attacks, by alienating the very communities on whom the government is most reliant for information.

Michael German, a former FBI agent who is now a national security expert at New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice, says wide-scale coercive recruitment produces a surfeit of false leads. “All of this investigative effort is against people who are not suspected,” he said, of “terrorism or any other criminal activity." The result is so much useless information that agents cannot focus on the most important leads. “This becomes an obstacle to real security.”

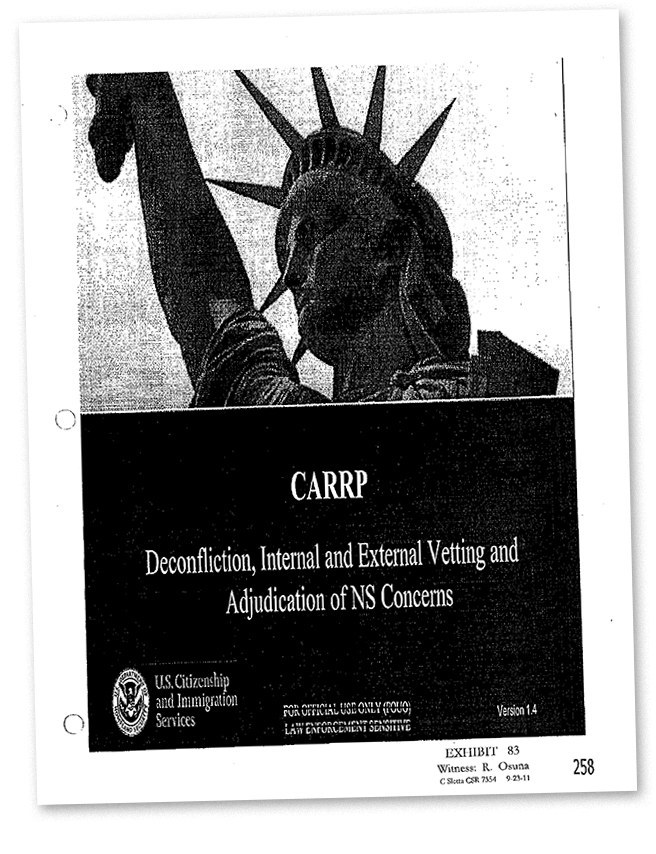

For immigrants pressured to become government informants, the process might begin with the Controlled Application Review and Resolution Program (CARRP). The program, overseen by immigration authorities, is designed to identify security risks among those who apply for visas, asylum, green cards, and naturalization. In November, BuzzFeed News revealed that the program is being used to vet refugees seeking asylum from Syria.

Initiated in 2008, and building on related efforts in the years before that, CARRP casts an extraordinarily wide net. It subjects not just “Known or Suspected Terrorists” but even “Non-Known or Suspected Terrorists” to intense scrutiny and potentially endless delays. Mere geography — hailing from “areas of known terrorist activity” — can qualify a person for this treatment. So can knowing someone, however tangentially, who is under surveillance; transferring money abroad; having ever worked for a foreign government; or even just having foreign language expertise. Despite these wide-ranging criteria, the results are remarkably consistent: According to scholars and immigration lawyers, the population caught in CARRP’s crosshairs is overwhelmingly Muslim.

Immigration officials will not reveal how many people currently fall under CARRP’s gaze, nor what fraction is Muslim. But the numbers are large: Just between 2008 and 2012, the case files of over 19,000 people from 18 Muslim-majority countries were rerouted through that program.

They were not apprised of their status. According to Christopher Bentley, a spokesperson for the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service, “There’s no notification sent to someone saying your case is being handled through this process.” All the person knows for sure is that the immigration application that should have proceeded along a predictable timeline has gone off the rails, flagged and delayed for years without explanation.

“Sometimes I joke, your immigration processing time is in proportion to the length of your beard,” said Hassan Ahmad, an immigration lawyer from Virginia. Over the course of 12 years he says he has represented clients from 112 countries. Only his Muslim clients, he says, encounter lengthy, unexplained delays.

In a 2014 lawsuit, the American Civil Liberties Union argued that CARRP is unconstitutional, violating the right to due process as well as the right to a timely review of immigration files as guaranteed by the Immigration and Nationality Act. (The five people on whose behalf the lawsuit was filed withdrew it when their applications were processed.)

After these extensive procedural delays, BuzzFeed News has learned, FBI agents like the ones who approached A.M. can take advantage of immigrants’ desperation — regardless of how useful their contacts would actually be, or what intelligence, if any, they have to offer. According to Charles Swift, a former Navy lawyer who won a Supreme Court ruling against the Bush administration’s policy of trying terrorism suspects in a military tribunal, the undisclosed role of law enforcement officials makes the process even more problematic. The immigration agency, at least, “ultimately will be accountable for its decisions in front of a federal immigration judge or a U.S. judge,” he said. But “the FBI is not accountable.”

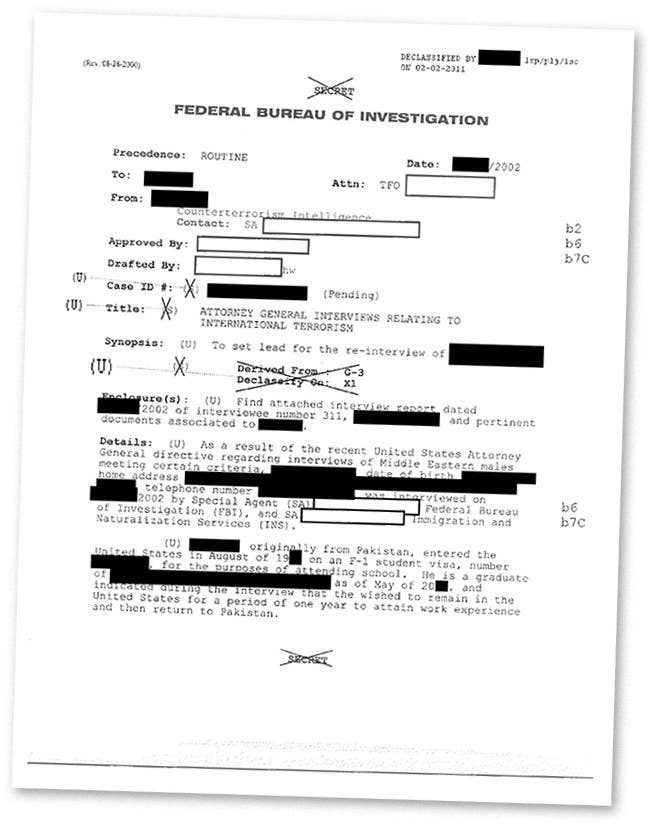

A.M. says the FBI knew he didn’t have any information about terrorists, because he already said so. Twice, in fact: first in the fear-stricken months after 9/11 and again in 2002 when agents approached him a second time. In his case file, which a lawyer was able to get ahold of, the agents noted that A.M. promised to let them know if he became aware of any suspicious activity. But in 2012 he did something less dutiful. He filed a lawsuit against the Department of Homeland Security, the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), and the FBI.

As he tells it, he had no choice: His green card application had been on hold for five years; his work visa was about to expire; and his senator, John Cornyn, to whom he had written for help, had responded that there was nothing he could do.

In very short order, immigration authorities revoked A.M.'s existing work visa, the one they had approved two years before. Later, four FBI agents turned up unannounced at his home, wanting to talk. He remembers one agent showing his badge and, perhaps inadvertently, revealing his gun. Others asked A.M.’s neighbors if he had any “violent tendencies.” (A.M. got the name of only one of the FBI agents. Agent Clay Huesman, who came to A.M.’s workplace that same morning to interview his co-worker, declined to speak with BuzzFeed News about the case, saying he was not authorized to do so.)

A.M. got in touch with Swift, the lawyer who had fought against military tribunals, who arranged a meeting at the Department of Homeland Security offices in Dallas.

It was there, tucked away in a room in a long, low-slung office building, that the officers pushed A.M. to become a secret informant. “They would want me to wear a wire,” he recalled, “go to my friends in the masjid, the mosque, talk about jihad, encourage them to fight or something, and then ask me to witness against them for provoking them. I can’t do that.”

He said he pleaded with the agents. “Is there something that you know about me? Then tell me. If there is something you think I have done wrong then tell me.” They didn’t answer. Instead, they told him that if he did not agree to their offer, he and his family would no longer be welcome in America.

Swift ended the meeting. Within hours, one of the agents called him and asked which flight his client would be on.

A.M. and his family sold what possessions they could, and two weeks later, they left the country that for 17 years he had called home.

Critics of CARRP say its entire premise strains credulity. If these immigrants posed a genuine threat to national security, wouldn’t authorities lock them up, rather than just allowing them to live for years at large in the United States? “They don't prosecute any of them, they don't even investigate them for real terrorist activities,” said Claudia Slovinsky, a 35-year veteran of immigration law. “If they really think someone is a danger, deal with it. Confront them.”

Because of the unique position that Muslim immigrants occupy in American national security — subjected to a higher degree of scrutiny but also solicited as valuable sources in their communities — CARRP can victimize Muslim immigrants twice: leaving them in painful limbo for years, and then exposing them to abuse by law enforcement.

Swift ticked off several cultural factors that may increase their vulnerability: “not strong in the language, not much money, not strong in due process concepts, and they often come from governments where if you don't play with the government, they can whisk you away and put you in jail.”

Critics cite another effect of the way the program is structured: CARRP has greatly expanded the FBI's influence in the immigration process, by giving the bureau immense sway in deciding who may and may not become citizens. In the 2013 report “Muslims Need Not Apply,” the ACLU reviewed public records, some of them heavily redacted, and found that immigration authorities “are instructed to follow FBI direction as to whether to deny, approve, or hold in abeyance (potentially indefinitely) an application for an immigration benefit.”

In an interview with BuzzFeed News, Bentley, the immigration press secretary, denied that, insisting that each individual’s file is reviewed — by immigration officials alone, not by law enforcement — on a “case-by-case” basis.

“CARRP is not a red flag that no one can overcome,” he said. “CARRP simply means that there is an issue here that needs to be resolved.”

He acknowledged that immigration officials and law enforcement officials do share their findings. “We utilize the FBI as a contract service and they provide us access to background information needed for us to make determinations on individuals’ immigration cases,” Bentley said. “But as far as exactly what the FBI does with follow-up from information that may be developed by USCIS, or ICE” — Immigration and Customs Enforcement — “or any other department within Homeland Security, only the FBI can speak to that.”

After almost a dozen requests over three months, the FBI’s National Press Office responded to questions from BuzzFeed News about the agency’s involvement with CARRP by supplying two links to the Attorney General’s Guidelines for FBI Confidential Human Sources, as well as the FBI’s Domestic Investigations and Operations Guide.

"Certainly we cannot confirm or comment on the specific approaches, tactics, or incidents involving recruiting human sources,” the public affairs officer added.

The first time Muhammad (his middle name) met with an FBI agent, it was in the lobby of the Hyatt Regency in North Dallas in 2010. An immigrant from Jordan who came to America in 1989, he had already been waiting for a decade to hear the results of his citizenship application. Muhammad brought two representatives of the Muslim American Society Immigrant Justice Center to the meeting. Agent Erik Tighe was accompanied by another agent from the bureau.

Over the course of more than two hours, Agent Tighe asked Muhammad about his relationship to the Holy Land Foundation.

Holy Land was a large and diverse Muslim charity — the largest in America — and Muhammad vaguely recalled signing up for a program to sponsor an orphan. The amount, he said, was at most $30. It was legal at the time, but the group was subsequently found guilty of aiding a terrorist organization. For a Muslim immigrant, Muhammad knew, even an accidental association like that could be fatal to any hope of ever becoming a U.S. citizen. According to Muhammad and his two advisers, Agent Tighe made an offer: Become an informant. Help the FBI. And the FBI will help with your immigration application.

The second time Agent Tighe approached Muhammad, he was less conciliatory. It was the morning of Jan. 5, 2011, at around 7:40 a.m. The FBI agent brought an official from the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, the agency that oversees immigration. They told Muhammad that if he didn’t work with them, they would delay his citizenship indefinitely.

“More than 10 years?” Muhammad said he asked. “More than that? You have already delayed it, so whatever you want to do, go ahead, but I’m not going to talk to you like this.”

BuzzFeed News attempted to reach Agent Tighe and other FBI agents mentioned in this story but was told by a spokesman that the FBI is “not doing interviews at this time.”

Muhammad eventually wrote a complaint to the Office of the Inspector General. “By using my charitable contribution as a means to determine my eligibility for naturalization, I have been designated a national security concern,” he wrote. “I am not. I am a law-abiding citizen who has an affinity to this country and would willingly protect it against any wrongdoing or criminal behavior.”

In February 2012, after 12 years, Muhammad’s citizenship application was denied because of lack of “good moral character,” an assessment based on his relationship to the charity. His future is uncertain. The supposed national security threat has so far been allowed to continue living in America, but his green card will expire in 2019. By that time he will have been in this country 30 years.

German, the former FBI agent, said that the FBI’s use of informants changed after 9/11. As the department’s priorities shifted toward counterterrorism, agents came under much greater pressure to develop Muslim sources — any Muslim sources, regardless of how useful they might actually be. Now, he said, “Rather than use all their energy to focus on the very small number of terrorists, they try to find anybody that they have a lever over to compel them to be an informants."

The issue has arisen before. A 2014 lawsuit filed by the Center for Constitutional Rights and a group at the City University of New York law school revealed that the FBI had been intimidating people on the no-fly list, saying they would never be removed unless they agreed to spy for the government.

After 9/11, said a recently retired former FBI special agent who spoke to BuzzFeed News on the condition of anonymity, the shift toward counterterrorism increased the “importance of having a lot of sources, especially within the Middle Eastern community. Naturally, most of those folks were immigrants.”

Dennis G. Fitzgerald, a former Drug Enforcement Agency agent with over 20 years of experience and the author of a book on informants and the law, concurred: “The leverage on an immigrant or an alien is unbelievable. It's all about having leverage on another human being, and using that leverage, that power, to persuade them, to squeeze them, into becoming an informant. ”

But however effective CARRP is as a recruitment tool for the FBI, there is little evidence that the arrangement has produced much usable intelligence.

Critics have questioned the government’s reliance on counterterrorism informants with mental illness or criminal records, as well as the ease with which investigation can become entrapment. “Informants who are pressured,” the former special agent said, “will just tell you what they think you might want to hear, or tell you something that will get them in a better position for himself, like getting immigration assistance.”

He continued, “They will tell you something that can’t be verified, or they’ll tell you something that they might think you want to hear. They will tell you there's something going on over here, or this person is planning this thing. And they will tell you that because they think it will help them in their particular situation, and not because it’s really happening.” The more false leads the FBI has to chase after, the fewer agents there are to track down the real ones.

Simple in dress and haircut, tall and slim, Osman (his middle name), a 38-year-old Somali refugee, blends in easily on the streets of America. He wears a pleasant smile for no reason at all. Those who pass him might assume he’s just as ordinary as he looks. But the path by which he came to this country is remarkable, and so is the threat that the federal government appears to believe he poses.

When Osman was 14, his father and two sisters were killed in the Somali Civil War. Osman made his way, by foot, to Kenya, along with hundreds of thousands of other refugees. He landed in what would become the world’s largest refugee camp, where he spent 14 years before getting permission to come to America.

“I was so excited. I was so happy. I used to watch movies about Las Vegas and Los Angeles, and I couldn’t believe I would ever live there,” he recalled.

Two years after arriving, in 2006, he decided to apply for a green card.

According to Osman’s immigration file — obtained by the ACLU on his behalf — immigration authorities ran him through the FBI’s Name Check database and came up with a hit. That meant Osman had been mentioned in some unspecified capacity in an FBI file. Or perhaps it was someone else with a similar name, or a phonetic variation of his name. Whatever the case, it was 2008, the year the CARRP program officially began. His application ground to a halt.

Three years after he filed the papers, he visited the local office of the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services to inquire about his status. Then he returned to his apartment, and 15 minutes later, Osman says, two FBI agents knocked on his door.

Over the next six months, the FBI agents repeatedly sought him out, asking him to identify photographs of men he told them he had never seen before or to talk about Ethiopian militants whom he tried to explain he knew nothing about.

One of the agents told Osman they had a deal for him. A “good deal,” Osman recalled: The FBI could help him with his green card application and even help some of his family immigrate to the United States.

But something changed, he said, when she called and said, “I want to ask you where Osama Bin Laden is.”

“That was when I got shocked,” he recalled. “I was really scared, and I was not feeling comfortable. She was giving me so much pressure. I think she was trying to scare me.” But he did not dare tell anyone in his community, lest someone think he was cooperating.

Immigration records indicate that right around that time, and again in March and May of 2010, the Joint Terrorism Task Force — a partnership of law enforcement agencies led by the FBI — requested information about Osman's immigration files from USCIS.

In March 2011, Osman was informed that his claim to be a member of Somalia’s persecuted Tuni clan “may have” been false. He tried to fight the charge, but lost. First his refugee status was revoked. Then, six years after filing an application for a green card, Osman finally got an answer: No.

An immigration lawyer did eventually get him in front of a judge, who ruled that the government had acted improperly. Osman’s refugee status was reinstated, and he even got a green card.

But when, encouraged by those developments, he applied to become a full citizen, he ran into the very same kinds of delays. FBI agents don’t show up at his door anymore, but he worries that he might still find himself searching for a country to call home. “I believe I'm already an American,” Osman said one recent night, sitting in a hotel lobby.

“I mean, I am an American!” he exclaimed, with his hands in the air. “This is my home. They might believe something else, but of course I am.”

America is no longer home for A.M., the software programmer from Pakistan who was told by the FBI agent to get out of the United States. Speaking with BuzzFeed News from the country where he and his family now reside — he asked that the country not be named, out of fear for relatives still living in America — he said he missed the place where he lived for 17 years. “We had a home there,” he recently wrote, “with close family friends, strong ties with the Muslim community, a vibrant life at the local mosque, and a stable job. Our lives were turned upside down when the Feds visited us on June 4th, 2014 7:45AM. Everything that was precious to us was in one way or another impacted by their unjustified and ruthless acts.”

He tried every possible way to resolve the suspicion of the government, he said. Nothing worked. When asked whether A.M. would have had a better chance of success if he were not a Muslim, from a Muslim-majority country, Claudia Slovinsky, the immigration lawyer, laughed. “He would be a citizen by now,” she said.